In my previous post, I went into detail on my plan to quantify the design of platformers at a broad level for analysis. This time, I’ll be going over the results of that analysis, and moving on from them. Last time was The Data-Driven Analysis of Platformers, and now we have:

Why It Didn’t Work

Turns out, nuance is an important thing. Sure, it sounds obvious in retrospect…

Anyway, first thing I did was look for some correlations. Unfortunately, I am no statistician, and freely admit I don’t know how to do that rigorously. So I took the spreadsheet, color-coded everything, sorted it a few different ways. Apart from games in a series often appearing to be fairly similar to each other, nothing jumped out at me. And that much wasn’t exactly interesting.

I also wrote a d3 script to take the data and allow it to be grouped and organized. Again, I didn’t see many patterns, and what I did find was mostly unhelpful.

As such, instead of directly presenting patterns from the data, I’m doing my best to salvage things: for each category, I’ve gone into detail on what nuance was lost by my too-rough analysis, and what patterns I can see through close examination, even if I can’t quantify them.

So, let’s go down the list, shall we?

Seriality and dimensions

The whole point of establishing a series is that the consumer knows what to expect, no? As such, it’s no surprise that games in the same series tended to have a lot in common. Unfortunately, that doesn’t give me very much information. Every metric was similar across all or almost all of the games in any given series.

One notable standout here was a correlation with the 2D/3D divide, which seems almost like a subseries: games in the same series most often had differences in metrics when one game was 2D and the other was 3D. This is a somewhat interesting design choice; 2D and 3D games are capable of presenting similar experiences, but developers of platformers seem not to want to go in that direction. This is more true in some cases than others, of course: compare Metroid games, which are usually fairly similar in gameplay, to Mario or Sonic, which have two fairly distinct blocks.

Dotted lines separate 2D from 3D games; solid lines separate series from each other.

In each series, we can see that some traits are consistent in a series, but others are much more common on (or exclusive to) either 2D or 3D games.

- 3D Mario games have at least a little bit of story and more varied layouts, mostly avoid ranged combat, and give some form of air-jump (which also provides improved air control).

- 3D Metroid games all give the player an air-jump early enough to count as “Yes” rather than “Slightly/Special” (though on the other hand, it’s much more limited than in the 2D games – this is a more granular than my data-collecting supported). They’re quite similar beyond that, though.

- 3D Sonic games have more linear gameplay, often remove jump-combat and water, provide an airjump, and have some emphasis on a story.

Genre savvy? Not so much.

Unfortunately, I didn’t have enough games here that could be classified with subgenres or secondary genres; when I did, they were mostly in the same series, which would tend to mask whatever commonalities were actually part of the genre.

There is insufficient data for a meaningful result here.

Plot and Player-Count: Mainly a Side Note.

The presence or absence of a story generally meant little for the rest of the gameplay: A story can be applied to, or witheld from, just about any game that doesn’t have its narrative as a major design focus. Additionally, many of the games listed here are from a time when technical limitations prevented there from being enough memory to fit a story into a game at a reasonable price, and most of the rest are in series that were established during that time. If narrative was never why people bought the game, it’s hard to justify the expense of hiring writers for the sequel.

There is the one interesting note that 3D Mario and Sonic games tend to include a story while the 2D ones avoid it, but that doesn’t seem to extend to 2D vs. 3D in general.

Multiplayer, too, has very little impact, for roughly similar reasons. It’s a tack-on much more often than it’s a core part of the game’s design. Most platformers don’t have it; when it is present, any influence it might have on the game design would have to be more abstract than these metrics. Many platformers that have a cooperative multiplayer mode treat it with a light-hearted tone, as well: more “friends romping around” than “everybody working together”, with the game as a whole designed more around the single-player experience. It was not a good decision to include multiplayer in this project; it’s a distraction, not a useful measure.

Getting the shape of things

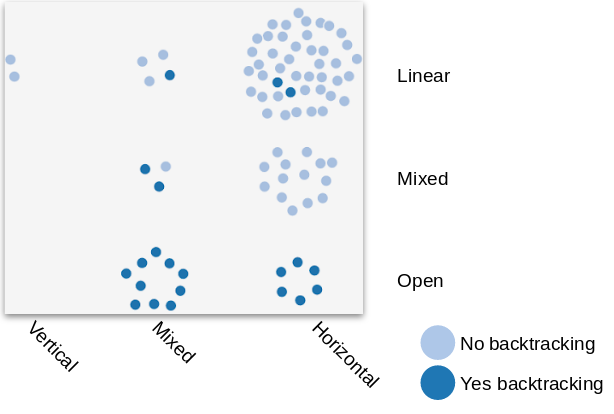

The next three had a noticeable – if obvious-in-retrospect – correlation. Using the graphing script from before, I sorted the games by their layout and the amount of player choice available, and then tried various color-codings. My results, with labels and a legend:

The games with more player choice tended to be of mixed layout, while both other categories of choice (and thus, the data as a whole) were majority-horizontal. Additonally, all open games had backtracking, while very few other games had it.

This might not be especially surprising, but I suppose it’s nice to see my intuitions confirmed.

Combat styles

The three different means of combat aren’t mutually exclusive, so they took up three fields in my chart, but practically speaking it only makes sense to consider them together. When I was assembling the list, I had a few ideas of what they might indicate – melee combat leading to a sort of heedless-charge, action-y style; ranged combat for something slow and exploratory, using cover or hiding; jumping combat for a game that’s really just about the platforming, with enemies used as temporary mobile obstacles or platforms rather than as something you actively fight.

Two of these predictions were incorrect, and the third was questionable.

My assumptions of pacing differences in melee and ranged combat seem to have been based on (poor, inaccurate, dim) recollections of specific games: 3D Sonic games for melee combat, and the Metroid series for ranged combat.

Taking them one at a time, here’s footage to illustrate why those assumptions don’t hold. Clips from one melee-combat game, one ranged-combat game, and one game that features a mix of both combat styles.

In Castlevania: Symphony of the Night, your main options for fighting are melee. Most enemies are also limited to melee combat; as such, fights tend to boil down to stepping forward and backward to dodge enemy swings (or using a shield, if your shield is good enough to block whatever you’re fighting) while stabbing back. It’s… at least slightly tense, and mostly about positioning. The game as a whole, though, is not about the fighting, but about the exploring; as such each individual monster is basically a speedbump, not especially difficult to defeat. They keep you more engaged than walking through an empty maze, and harder enemies keep you out of areas you’re not equipped for (while also emphasizing how much better your new gear is, when you’re ready to return).

In Metroid II: Return of Samus, combat is again mostly not the point, and enemies are mostly obstacles. It’s structured a bit differently from Castlevania: SOTN; enemies are easier to avoid, rather than fight through, but either way mostly just slow you down and provide atmosphere. Return of Samus is actually a bit more combat-focused than most other Metroid games, in that there are forty-odd required boss or mini-boss fights against half a dozen different types of the titular “Metroids”. Even so, it’s much more about the hunt through claustrophobic caves, and the atmosphere of a mission somewhere between extermination and genocide (for context, think of a real-world attempt to force the extinction of, say, a species of bear as smart as a particularly clever dogs, after some organization trained a few of them to attack people), and much less about the relatively short battles when you find the things.

In Kirby’s Dream Land 2, you have both melee and ranged combat options. Most enemies are dispatched in one hit, though – they’re minor obstacles, something to stop you from just sprinting across the whole level. The bosses and mini-bosses are more challenging, but are still more about dodging than the details of how you hit back. Interesting gameplay there comes mostly from the optional two-part puzzles: find where the shiny secret thing is, then determine how to get there while using a specific power and companion, which might not be available nearby and might have interesting movement restrictions to make the path harder.

To be clear, my point here is not that these games are representative of all combat-styles, but that the combat style does not make for a reliable predictor of much else about a game.

The idea I had for jumping combat seems to have been relatively accurate, but since the time I compiled this dataset, I’ve heard of at least one game (Downwell) that shows it’s not a perfect summary.

It may not have made it on the list, but Downwell is a platformer that takes place largely in freefall: while you do have a gun in addition to the option to stomp enemies, that gun only shoots down, so you’re still lining up jumps (from one head to the next) as the core of the combat.

Compare that to Donkey Kong Country: Tropical Freeze:

This is very much the sort of game I was thinking of in my earlier analysis: “enemies” serve mainly as things to jump over or bounce off of, rather than as something to fight. They’re in the way, but they’re easily avoided and nonthreatening.

Collectibles, hidden and sought

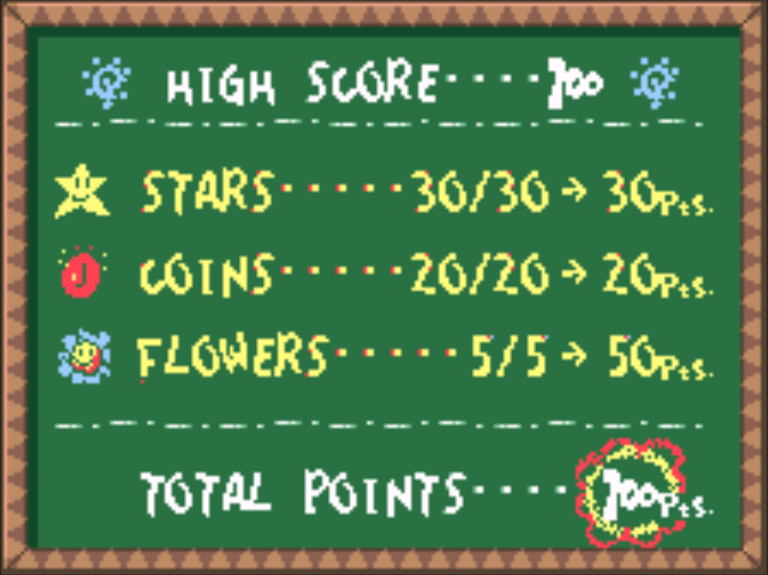

Collectibles, as measured here, are perhaps the worst case of lost nuance in my dataset. In some games, such as the original Yoshi’s Island or the New Super Mario Bros. sub-series, finding all the hidden things is a goal in and of itself. They’re all over the place (Yoshi’s Island has twenty-five; New Super Mario Bros. has three), and finding all of them unlocks even more levels, the hardest in the game. These games use collectibles as a way for the player to prove their mastery, and then reward the player with more challenges to master.

In others, such as most “Metroidvania” games, collectibles take the form of small upgrades (usually for health, ammunition, or similar). These games usually show you a counter or percentage, and might give a special congratulation at the end for 100% completion, but the main reason to hunt them down is that they make the game easier (or that you find them while looking for something else). They’re not required, and in fact, players looking for a challenge are as likely to go for a no-upgrade run as they are to aim for 100%. In this case, finding them all is about persistence more than anything else, and the journey is most of the reward, because anyone who’s played the game enough to find all the upgrades is unlikely to actually need them. Still, the fact that each one provides some tangible benefit can get players to look – or, at least, to enjoy incidental finds – when the journey isn’t enough on its own.

Still other games put collectibles front-and-center; this is a defining trait of “collectathons”, which were a major subgenre of early 3D platformers that haven’t gone away completely. In this case, finding all the hidden things is the entire point; the nominal “goal” of the game as described by whatever plot there is (usually minimal) is reached long before finding everything, and the miscellaneous shinies you’re hunting down are as likely to be on the other side of a tricky gauntlet of difficult jumps as they are to be under a random bush five feet behind your starting location. There may be rewards given at various increments – usually unlocking new areas to explore – but these will eventually run dry. The journey is the destination again, but this time without much pretense of any other reason to search, so those players who aren’t motivated by completionism are likely to stop before the end.

Three approaches to the power-up

Power-ups were another badly-defined grouping. In some cases – Mario and Sonic come to mind for their high variety – power-ups are a way to make the game temporarily easier, until you mess up. A few seconds of invincibility (traditionally with music), is a common one across a variety of games. Sonic games often provide shields with side-effects, Mario games tend more towards costumes (that look like miscellaneous objects until used). In both of these cases, and some others, power-ups are treated by the game design as a prize, and a bit of relief: find them, and things get a bit easier for a while.

On the other hand, Kirby games (for example) treat power-ups more like equipment. They’re not required, but they’re not hidden prizes, either: you can find them all over the place, there’s a wide variety of powers, and you only rarely need to have any specific one (usually for optional challenges, where the challenge is “how do I get to this place without losing this power” rather than having to do anything particularly tricky when you get there). The games tend to be built around the assumption that you’ve got something, without caring about what it is. Another game that demonstrates this pattern (though they’re not as heavily emphasized there) is Castlevania: Symphony of the Night (specifically, the sub-weapons). In both cases, powers aren’t required, and they aren’t (usually) a prize; they’re just one more thing to mess around with.

In yet a third group, some games will shove a power-up at you at the start of a section, which provides a major change in the gameplay while it lasts. You can’t beat the level without that boost, and it won’t be given where it isn’t necessary. One example of this is the Feather in Celeste:

The Feather gives Madeline (the redhead) the ability to fly for a few seconds. Most of the areas with a Feather in that game require her to fly efficiently around obstacles from each Feather to the next, before running out of time and falling. This also appears in some levels of Yoshi’s Island, which turn Yoshi into various vehicles at the starting-point of a section, and teleport him back there if he can’t reach the end before a time limit. For example, the third “Secret” level in the GBA remake is focused entirely on such transformations.

Submersive diversions

Swimming is generally treated by most platformers as something similar to the third kind of power-up: a section of the game that plays differently from the rest. Where water is present in a game, and not treated as an instant-death hazard, there’s two common ways of handling it (and one less-common), plus one optional addendum.

First, and most-common in my experience, is the free-swimming approach. You go in the water, and you can swim around as you like. Some games do this by slowing movement and replacing “jump” with “swim up a little”, leaving the controls otherwise unmodified; other games let you swim in any direction using the usual direction controls, with “jump” becoming “swim a little faster”. The former approach is more common in 2D, and the latter in 3D.

Second is sinking. In this case, water reduces movement speed and (usually) increases jump height, but the character can’t swim, and instead just sinks to the bottom.

Either of these are sometimes, but not always, combined with a drowning risk – if you stay underwater for too long in one go, game over. Usually, there’s air bubbles or something to extend the time limit; some games will technically have a time limit but rarely have a water section long enough for it to matter.

Finally, and rarest, is floating. The character floats on the surface of the water, and can’t swim under. This is presumably rare because of how little it offers in gameplay, relative to simply having solid ground. Most often, this combines with either limits on what can be done while floating (e.g. no carrying objects, or no attacks), or involves the use of momentum to dive for a short time before floating back up (find somewhere high to fall from so that you can get through an underwater passage). This appears near the start of the Yoshi’s Island video in the previous section (rewind to before where it loads). I couldn’t find a better clip – as I said, this is rare.

Unusual modes of mobility

Air-jumps, air-control, and wall-jumps. The most physically plausible of these was also the last to come to platformers: air-jumping and air-control give the player more control over what they’re doing, while also being fairly trivial to add to a game in development: just don’t bother checking whether the character is on the ground when the player tries to move or jump! Those have been around for ages. The presence or absence of air-jumping makes for serious differences in level design. On the other hand, these days, air-control will certainly be present, the only question being one of scale.

Wall-jumping, on the other hand, is a whole new thing – still around for ages, but slightly shorter ones, and there’s plenty of games that deliberately don’t have it or limit it. The addition of a walljump adds entirely new questions: what angle do they jump at, and how fast? Should it be straight up, usable to climb a wall, or do you need two walls close together to bounce between? Or is it nearly horizontal, so you can’t gain height with it, only move laterally? If you’re close enough to a wall to jump, can you slide down it to fall slower? Different games handle this in a variety of ways – notably, Super Metroid, the first in the series to have wall-jumping in it, doesn’t tell the player about it directly. The only way to find out is when the game leads you to get stuck at the bottom of a pit, at which point some small animals demonstrate the concept (leaving the actual controls required to trial-and-error). Most games are better about it than this.

Still, for all three of these, presence-or-absence (or strength, for air control) isn’t enough of a measure. The New Super Mario Bros. games all have wall-jumping, pretty good air control (just a shade below what I would have called “strong”), and all but one provide limited air-jumping in the form of various power-ups, depending on the game. Nevertheless, they only rarely give you any walls worth jumping off of (the number of times it’s actually required can be counted on one hand), never require complicated midair maneuvering, and only require the use of air-jumps for occasional collectibles (of the “prove your skill” kind).

Celeste also has wall-jumping, air control, and air-jumping (strictly, air-dashing: a short boost in a straight line, rather than following jump physics). Unlike in New Super Mario Bros., though, nearly every screen in all of Celeste is going to require all three.

How do we make difficulty measurable?

The question on my sheet for “leeway for error” was an attempt to make “this game is hard” less of a subjective statement. I initially got the idea from a blog post by “Ghoul King”, but have since found similar ideas cited earlier by the game-design show Extra Credits in “When Difficult Is Fun”.

The basic idea here is that what makes a game “hard” can be split into two parts: “This bit requires a lot of skill or many tries” (jumps to tiny platforms, fast-moving enemies to dodge or fight, etc.) and “I have to do a dozen things in a row without messing any of them up once”. The former is challenging; the latter is punishing.

A challenging game pushes the player’s skills. In Yoshi’s Island, maybe you need to bounce a throw off a wall (or three) to hit an enemy behind you, or dodge enemy projectiles in free-fall, or get across a temporary bridge before the timer runs out. However, in most cases, messing up won’t make you redo anything you’ve already done: you drop Baby Mario and have to run to grab him before time runs out, but you don’t get tossed back to the last checkpoint unless you do run out of time. Additionally, you have to wait a few seconds after the recovery for the timer to refill, there’s no timer unless you drop the baby, the auto-refill doesn’t go over ten seconds (the max is thirty), and you get scored at the end based on (in addition to your collectible count, as mentioned in the section on collectibles) how much time you had left on it. The first two points push the player to take their time; the others emphasize avoiding mistakes, but generally don’t make it hurt too much if you make them.

By the end, the game’s got the player doing some pretty fiddly stuff – but never required to rush, and always given plenty of chances.

On the other hand, a punishing game requires you to avoid mistakes for long stretches at a time. The epitome of this, for me, is Celeste. Each screen has increasingly-precise jumps, tight passages full of spikes, wide gaps you can barely get over, and so on; you’re given less and less stable ground to stand on the farther you go, and even if you do find a place to stop and take a breath, messing one jump up sends you back to the beginning of the area. No one screen will take more than about thirty seconds or so, but by the time you can beat it once, you’ll probably have spent minutes or hours redoing the earlier bits, pushing your death forward by a second (or less) at a time. On the other hand, that one culminating run where everything went exactly right is definitely a rush.

These are two very different kinds of difficult games, but unfortunately, my metric of “leeway for error” only covers how punishing a game is.

- Most Kirby games are neither punishing nor challenging, and when they diverge from this, it’s generally by adding a boss-rush (making you fight every boss in the game with limited healing in-between). Even if the individual fights are easy, small slip-ups add up over ten to nineteen consecutive bouts (depending on the game), so that’s punishing.

- Celeste starts off more punishing than challenging, but by the end, it’s got both in spades.

- Most of the 2D Mario games are moderately punishing (to varying degrees) but only mildly challenging (so it doesn’t really matter, practically speaking, how punishing they are).

Pushing the boundaries

This next bit moves ever-farther from my original analysis, but it was also one of my early goals that proved incompatible with a data-driven view. On the other hand, that’s well out the window by now.

It seems interesting to have a look at some games that push the boundaries of “platformers”. Three came to mind. One, Owlboy, made it into my original dataset. One, Downwell, got a mention earlier, in the combat section. The third, Snake Pass is here only. All three make major changes to what seems to be the most fundamental mechanic in a platformer: the jump.

In Owlboy, you play as Otus, who is one of many owl-people who live on a flying archipelago (there’s quite a lot of story). As such, you can fly freely for nearly the entire game (except for a few scenes that take place in rainstorms). Nevertheless, the nature of the game as a platformer isn’t just a stylistic variation on, say, old top-down RPGs (where the environment is mostly just a background for the game). Maneuvering among obstacles and through passageways, often while solving puzzles or battling pirates, is a core part of the gameplay, even though gravity is mostly irrelevant to your own movement. You may not need to worry about falling into pits or onto spikes, but you do still need to maintain a keen awareness of your movement and surroundings; traversal is still core to the game.

Downwell is a platformer initially designed for mobile phones, and is meant to be played with the phone held in “portrait” orientation. As such, it’s one of the rare platformers to be largely vertical; even more unusually, it’s the only such game I know of to be about falling rather than climbing. In Downwell, you are falling down a monster-infested well, with guns strapped to your feet. Ammunition is very limited, but is refilled every time you land on an outcropping or an enemy. Shooting doubles as a way to slow your fall (with the recoil). That plus a combo system is the core of the game; it’s a mobile game, so depth-from-simplicity is the order of the day. This one is probably the least questionable to consider as a platformer, and the one that pushes the definition the least; sure, it’s more about falling than jumping, but you’re still carefully aiming your fall, and frankly there’s nothing preventing something like this from being a level in any number of existing platformers.

Finally, Snake Pass. Where Owlboy replaced jumping with flying, and Downwell moved focus away from the jump and onto the fall that follows, Snake Pass has no jumping whatsoever. In Snake Pass, you are Noodle, a snake (apparently a coral snake, going by the banding). Snakes cannot jump, but they can climb. It’s a very different sort of platformer, and pushes the limits as much or more than Owlboy, though in a different direction. Where Owlboy has freewheeling acrobatics and light gunplay, Snake Pass has carefully wrapping around sticks and poles, hunting for various treasures while being sure not to fall, and no combat whatsoever. It could be called a delicate balancing act, except that if you’re trying to actually balance on anything you’re already doomed, because you’re a snake. Get a grip, that’s the way to do it. Metaphorically, though, it works. On the one hand, you’ve got friction; on the other, gravity. Your tail holds you up and pulls you down, all at once. It’s a fiddly game, and one of the few in either this post or my collected data which I’ve had the opportunity to start, but haven’t had the skill to finish.

Bringing it back around to the start

These two posts are, at least nominally, a class project. And the topic of the class, in the end, is originality, derivation, influence, and so on. It’s difficult to apply many of the ideas from the class to game design; the process of making a game usually involve many people, often without any one person taking sole credit for making creative decisions. Any of these people may have different experiences, both in terms of preexisting games they might draw from, and in terms of anything else from which the creators might take inspiration*.

*(lighthearted) Yes, Professor, I know you don't like the word "inspiration", but I firmly believe the etymological implication of divinity is long-ago-and-far-away, and the use "takes inspiration from" avoids the grammatical who-has-agency issue.

Nobody in game design would ever claim to stand apart from preexisting works, not and expect the claim to be taken seriously. It’s just that there’s so many games, and very few people have the time to play a significant portion of them, let alone analyze everything; the specific originator of a given idea is very difficult to pin down. That goes doubly so when the design element in question wasn’t a major focus of the game, when you have to distinguish between the first game to do something and the first game to do it well, or when something started out as a glitch.

For an example, take wall-jumping: In my dataset, Super Metroid was the earliest game to have it, but Super Mario 64 was the first game to actually tell the player about it clearly. I don’t know of any earlier game that intentionally included it, but I do know that many older platformers, including (but not limited to) the original Super Mario Bros., technically had walljumping due to a glitch: The world is built up from tiles, and so the top corner of tile in a wall could be treated as a floor, if you hit a wall exactly at the border between tiles.

Is that, then, a first source for wall-jumping? It’s certainly possible that the developers of Super Metroid may have known of a wall-jump glitch in any of the many tile-based platformers that existed at the time. However, I can’t find information on how widely-known the glitch was at the time in any given game, and the idea could just as easily have come from exaggerating real-world feats of athleticism.

For another example, Snake Pass again. Certainly, the cartoony aesthetic and collectathon gameplay of clearly call back to the 3D platformers of the late 90s and early 00s. However, the notable bit about the game – the fact that you are a snake, who moves in roughly the manner of real snakes – has been stated by the original designer to have two sources.

- A mistake in a tech demo.

- Actual snakes.

Seb Liese: When Sumo Digital gave me a small period of time to try to learn Unreal Engine, one of the things I tried to make early on was a rope that would move when a player touches it. As I was creating this rope, I pressed the play button and had forgotten to attach it to the ceiling. When I saw it fall on the floor in this really nice smooth shape that collided with itself I thought back to my background as a biology teacher, when I had two pet snakes, and I instantly thought ‘hey, this could be a snake!’ The Making Of Snake Pass – interview by Nintendo UK with Seb Liese

There’s so much out there, and so many things being made concurrently, that I have no real way to tell whether a design choice was based on a particular preexisting game, was part of a general zeitgeist, or developed from a chain of coincidence. At least, not unless someone on the design team has gone on record – and even then, if it’s years after the game’s release, people have been known to contradict themselves and each other.

Interesting, novel choices are more likely to result in an interview leading to such a thing being on record, but that’s still no guarantee. In the Snake Pass example above, the same design could have come from entirely different sources: perhaps the chain would go something like “What if you had a platformer with no jumping? Well, just walking is boring. What moves in a more interesting way than walking? Snakes!” We have Liese’s word in that interview that it wasn’t like that, that it started with a snake and then developed along the question of what would be entertaining to do as a snake. Without that, though, there’s so many different elements in a game that need to fit together, and no real way to know which one came first, which had to bend to allow the others to work.

The specific terms taught in class often revolve around intent – the intent to “swerve” from established patterns, or parody them, or uphold them, for example. Business concerns rarely came into the picture How does one tell apart a game sticking to the patterns to appeal to an established market, from one that aimed for novelty but ended up too subtle for most people to tell? A planned feature that had to be cut to make deadlines, but which left evidence of its existence in old marketing materials? A glitch in development that turned out fun enough to leave in?

The metaphor used in class was to a billiards table, but the scope of games in general and my project in particular means that there’s a hundred cues, held by a dozen people each, and nobody’s taking turns. If I had looked more closely at a small set of games, I might be able to come up with a plausible lineage for the ideas therein. However, doing so would give me no assurance as to my accuracy, and I believe that more is gained in this scenario by looking at what patterns are generally widespread. This is not to say that there’s no benefit in looking closely at a few things, but if you’re looking for a lineage without knowing what the designers actually thought and meant, it seems to me that you’re just telling myths: it sounds nice, and it makes your point, but there’s nothing to say whether the tale is actually true.

In the end, I think I’ve established the existence of plenty of patterns, plenty to demonstrate that the game-development industry is looking at existing games (and other things) in the process of making new ones. Classifying the nature of the looking, or establishing a clear lineage of any given idea, is far beyond me.